Unlocking Equine Wellness:

The Power of Applied Kinesiology

Applied kinesiology is an innovative approach that combines the principles of muscle testing and holistic health practices to address various issues in horses. This method is gaining recognition for its effectiveness in diagnosing and treating a range of behavioral and physical problems in equines. Here’s how applied kinesiology is transforming horse care.

Understanding Applied Kinesiology

Applied kinesiology involves assessing a horse’s muscle function and overall physical condition to identify imbalances or dysfunctions. By understanding how a horse moves and interacts with its environment, practitioners can pinpoint underlying issues that may be affecting performance or behavior.

Key Benefits of Applied Kinesiology

- Holistic Assessment: This approach considers the horse as a whole, examining physical, emotional, and environmental factors that contribute to its well-being. This comprehensive view allows for targeted treatment plans.

- Identifying Imbalances: Through muscle testing and movement analysis, practitioners can identify specific muscle weaknesses or imbalances that may lead to pain or behavioral issues. Addressing these imbalances can improve the horse’s overall performance and quality of life.

- Customized Treatment Plans: Applied kinesiology provides tailored strategies to address individual horse needs, which may include massage, stretching, and specific exercises designed to strengthen weak areas and improve flexibility.

- Behavioral Insights: Many behavioral issues stem from physical discomfort or stress. By resolving physical imbalances, applied kinesiology can help alleviate anxiety, aggression, and other unwanted behaviors, leading to a more harmonious relationship between horse and handler.

- Preventative Care: Regular assessments can help catch potential issues before they develop into serious problems, ensuring that horses remain healthy and performing at their best.

Techniques Used in Applied Kinesiology

- Muscle Testing: This technique helps identify weak or dysfunctional muscles, guiding practitioners in creating effective treatment plans.

- Movement Analysis: Observing the horse in motion allows practitioners to assess gait, posture, and overall movement efficiency.

- Manual Therapy: Techniques such as massage and stretching are used to relieve tension and improve muscle function.

- Rehabilitation Exercises: Custom exercises are designed to strengthen specific muscle groups and improve overall balance and coordination.

Case Studies and Success Stories

Many horse owners have reported significant improvements in their horses’ health and behavior after utilizing applied kinesiology. Common outcomes include:

- Enhanced performance in competitive horses

- Reduction in anxiety and stress-related behaviors

- Improved mobility and flexibility, reducing the risk of injury

Conclusion

Applied kinesiology is leading the way in the holistic treatment of horse problems by addressing the root causes of physical and behavioral issues. By focusing on the whole horse and employing targeted techniques, this approach not only enhances performance but also promotes a healthier, happier life for equines. For horse owners seeking effective solutions to their horses’ challenges, applied kinesiology offers a promising path to well-being and improved relationships.

Understanding Equine Attunement: A Holistic Approach to Horse Care

Horses are incredible creatures, each with their own unique personalities and behavioral quirks. As equestrians and horse lovers, we often find ourselves faced with behavioral challenges that can be puzzling and frustrating. This is where Equine Attunement comes into play, offering a holistic approach to understanding and resolving these issues by addressing their root causes.

What is Equine Attunement?

Equine Attunement is a practice that emphasizes the deep connection between horses and their humans. It focuses on awareness and sensitivity to a horse’s emotional and physical state, helping owners recognize the signs that something might be amiss. Rather than merely treating symptoms, Equine Attunement encourages a comprehensive understanding of a horse’s needs, fostering a healthier relationship between horse and rider.

The Importance of Holistic Care

Holistic care for horses means considering all aspects of their well-being—physical, emotional, and environmental. Just as we wouldn’t treat a headache without exploring potential underlying issues, we shouldn’t overlook the complex interplay of factors affecting a horse’s behavior.

Physical Health

Behavioral issues often stem from physical discomfort. For instance, a horse that refuses to cooperate may be experiencing pain from an undiagnosed injury or ill-fitting tack. By taking a holistic view, we can identify and address these physical ailments, allowing for more positive interactions.

Emotional Well-being

Horses are sensitive animals, capable of experiencing a wide range of emotions. Stress, anxiety, and fear can all contribute to behavioral problems. Equine Attunement encourages us to recognize these emotional signals and create a supportive environment that promotes trust and safety. Techniques such as mindfulness and gentle handling can help alleviate emotional distress.

Environmental Factors

A horse’s environment plays a significant role in its behavior. Factors like social dynamics within a herd, housing conditions, and training methods can greatly influence how a horse behaves. Equine Attunement involves assessing these environmental elements and making necessary adjustments to ensure a more harmonious setting.

Techniques Used in Equine Attunement

Equine Attunement employs various techniques to enhance communication and understanding between horse and rider:

- Mindfulness Practices: Being present and aware during interactions with horses helps identify subtle cues and signals.

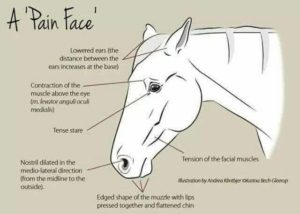

- Body Language Interpretation: Understanding a horse’s body language is crucial. For example, ear position, tail movement, and stance can reveal a lot about a horse’s feelings.

- Energy Work: Techniques like Reiki and other energy healing practices can help balance a horse’s emotional state and promote relaxation.

- Groundwork and Connection Exercises: Building a strong foundation through groundwork helps establish trust and respect, which are essential for effective communication.

Why Choose Equine Attunement?

For those passionate about horse care, Equine Attunement offers a transformative approach that goes beyond traditional training methods. By focusing on the root causes of behavioral issues, horse owners can cultivate a deeper bond with their equines, leading to improved behavior, performance, and overall well-being.

Whether you are a seasoned equestrian or a new horse owner, incorporating Equine Attunement principles into your practice can make a significant difference in how you relate to your horse. By fostering awareness and understanding, you can create a more compassionate and effective partnership.

Conclusion

Equine Attunement is not just a methodology; it’s a philosophy that places the well-being of the horse at its core. By addressing the underlying causes of behavioral issues through a holistic lens, we can nurture happier, healthier horses and stronger human-equine relationships. Embrace this journey of awareness and connection, and watch as your bond with your horse flourishes.

Meridian Lines and Acupuncture Points in Horses: A Holistic Approach to Equine Health

Understanding the concept of meridian lines and acupuncture points can significantly enhance the well-being of horses. These principles, rooted in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), focus on the energy flow within the body and how it influences physical and emotional health.

The Five Elements in Horses: Understanding Their Influence on Health and Behaviour

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the concept of the Five Elements—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water—plays a crucial role in understanding the balance and health of living beings, including horses. Each element corresponds to specific characteristics, emotions, and physiological functions. Here’s a closer look at each element and how it relates to equine health and behaviour.

1. Wood

- Associated Organs: Liver and Gallbladder

- Characteristics: Growth, flexibility, and vitality.

- Emotions: Anger and frustration.

- Influence on Horses: Horses influenced by the Wood element tend to be energetic, strong, and assertive. They may become easily frustrated if their energy is not channeled properly, leading to behavioral issues such as rearing or biting.

2. Fire

- Associated Organs: Heart and Small Intestine

- Characteristics: Passion, joy, and communication.

- Emotions: Happiness and excitement.

- Influence on Horses: Fire horses are often lively, enthusiastic, and social. They thrive on interaction and can become anxious or agitated without stimulation. Balancing the Fire element helps in managing stress and excitement levels.

3. Earth

- Associated Organs: Spleen and Stomach

- Characteristics: Stability, nourishment, and grounding.

- Emotions: Worry and overthinking.

- Influence on Horses: Horses with strong Earth traits are usually calm, reliable, and nurturing. They may struggle with digestive issues if their environment is unstable or if they experience emotional stress.

4. Metal

- Associated Organs: Lung and Large Intestine

- Characteristics: Structure, discipline, and clarity.

- Emotions: Grief and sadness.

- Influence on Horses: Metal horses tend to be disciplined and focused. However, they can also be sensitive and prone to respiratory issues if their emotional state is not balanced. Ensuring they have a supportive environment helps maintain their well-being.

5. Water

- Associated Organs: Kidney and Bladder

- Characteristics: Fluidity, adaptability, and wisdom.

- Emotions: Fear and insecurity.

- Influence on Horses: Water horses are often intuitive and adaptable but can become fearful or anxious if their surroundings are unpredictable. Supporting their emotional needs helps foster confidence and resilience.

Conclusion

Understanding the Five Elements in horses offers valuable insights into their behavior, health, and emotional well-being. By recognizing how these elements interact and influence each horse, owners can create a more harmonious environment that supports their equine companions. Incorporating this knowledge into care routines—whether through nutrition, training methods, or holistic practices—can enhance a horse’s overall quality of life.

Bridging the Gap: Why Equine Kinesiology is Essential in Horse Care

In the world of equine care, we have an impressive array of specialists: veterinarians for physical issues, dentists for dental health, chiropractors for spinal alignment, bodyworkers for muscle release, and farriers for hoof care. However, a crucial component has often been overlooked—the emotional and metaphysical well-being of our horses. This is where equine kinesiology, also known as applied kinesiology, steps in to fill the gap.

Equine kinesiology focuses on the interconnectedness of the body, mind, and spirit in horses. This holistic approach seeks to identify and address emotional and metaphysical issues that may be affecting a horse’s overall health and behaviour. By understanding that emotions drive behaviour, we can begin to see how unaddressed emotional challenges can lead to physical ailments or undesirable behaviours.

Horses are incredibly sensitive creatures, often mirroring the emotional states of their handlers and the environment around them. When they experience stress, trauma, or anxiety, these emotions can become trapped in their bodies. If left untreated, these trapped emotions can manifest in various ways, such as:

Equine kinesiology represents a vital missing piece in the puzzle of horse care. While we have specialists to address physical health, the emotional and metaphysical aspects are equally important. By incorporating applied kinesiology into your horse care routine, you can unlock a deeper understanding of your horse’s needs, leading to improved behaviour, enhanced performance, and overall well-being.

As we continue to evolve in our approach to equine care, let us not forget the importance of nurturing the emotional health of our horses, ensuring they lead happy, fulfilling lives alongside us.

Why Do Horses Act Weird Sometimes? Understanding Displacement Behaviors

Have you ever seen a horse suddenly start yawning, scratching itself, or licking and chewing, especially when nothing exciting is happening? It might look random, but these actions can actually mean something important!

What is Displacement Behavior?

Displacement behavior happens when a horse feels unsure, stressed, or caught between two choices. Instead of reacting directly, they do something that seems out of place, like licking their lips when they are not eating or shaking their head when they’re not annoyed by flies. It’s their way of dealing with confusion or pressure.

Common Displacement Behaviors in Horses:

- Yawning – Not just for bedtime! Horses yawn when they’re stressed, frustrated, or trying to relax after excitement.

- Licking & Chewing – This can be a sign they’re thinking or feeling a bit unsure.

- Scratching or Grooming – Themselves. Ever seen a horse suddenly scratch its side or nibble at its leg? It might be a way to release nervous energy.

- Sniffing the Ground – Sometimes, a horse will pretend to be interested in the dirt when they’re actually feeling uncertain.

- Pawing the Ground – This can mean impatience, but it’s also a way to deal with frustration.

Why Do They Do It?

Horses show displacement behaviors when:

They’re not sure what to do next.

They feel stressed or pressured in training.

They’re nervous or excited.

They’re processing new information.

What Can You Do?

If your horse shows displacement behavior, take a step back and check what’s going on. Are they confused? Feeling pressured? Giving them time to figure things out and using clear, kind training can help them feel more confident.

Next time you see a horse doing something that seems random, look closer – it might just be their way of telling you how they feel!

Exploring Wisdom Through Literature:

Warwick Schiller’s Recommended Reads

Warwick Schiller frequently highlights the transformative power of great literature in shaping our understanding of horsemanship, personal development, and life itself. Below, you’ll find some of his top recommendations, each offering unique insights and inspiration for those looking to deepen their knowledge and enhance their journey with horses and beyond. Whether you’re an experienced equestrian or just beginning, these titles are sure to enrich your perspective and ignite your passion. Let’s dive in!

Warwick Schiller Book List:

Evidence Based Horsemanship – Martin Black & Steven Peters

Don’t Shoot the Dog – Karen Pryer

The Culture Clash – Jean Donaldson

The Other End of the Leash – Patricia McConnell

Tipping Point – Malcolm Gladwell

Outliers – Malcolm Gladwell

David and Goliath – Malcolm Gladwell

Blink – Malcolm Gladwell

What the Dog Saw – Malcolm Gladwell

Mastery – Robert Greene

Talent Code – Daniel Coyle

The Rise of Superman -Steven Kotler

Stealing Fire – Steven Kotler & Jamie Wheal

Rising Strong – Brene Brown

Daring Greatly – Brene Brown

I Thought It Was Just Me – Brene Brown

The Power of Vulnerability – Brene Brown

Dare to Lead – Brene Brown

Recovery – Russell Brand

10% Happier – Dan Harris

Mindhacking – Sir John Hargrave

The Biology of Belief – Bruce Lipton

You Are The Placebo -Joe Dispenza

Mind to Matter -Dawson Church

Polishing the Mirror – Ram Dass

Untethered Soul -Michael Singer

Waking the Tiger – Peter Levine

In An Unspoken Voice – Peter Levine

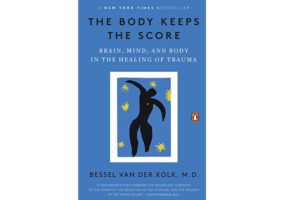

The Body Keeps The Score – Bessel Van Der Kolk

Metahuman – Deepak Chopra

The Way of the Peaceful Warrior – Dan Millman

The Alchemist -Paulo Coelho

The Celestine Prophecy -James Redfield

The Masks of Masculinity – Lewis Howes

Backbone – David H Wagner

Gamechangers – Dave Asprey

The Sense of Being Stared At – Rupert Sheldrake

A Kinship with All Life- Allen Boone

The Wedge – Scott Carney

The Emotion Code for Horses: A Path to Healing and Well-Being

The Emotion Code, developed by Dr. Bradley Nelson, is a healing technique designed to identify and release trapped emotional energies that can negatively impact physical and emotional health in both humans and animals. When applied to horses, this approach can lead to profound transformations, improving behavior and overall well-being.

Understanding the Emotion Code

The Emotion Code operates on the principle that unresolved emotions can become trapped in the body, leading to various physical and emotional issues. Horses, being highly sensitive animals, can experience emotional trauma just like humans, which may manifest in behaviors such as:

- Anxiety or fearfulness

- Aggression or irritability

- Reluctance to perform tasks

- Withdrawal or depression

How the Emotion Code Works

- Identifying Trapped Emotions: The process begins with muscle testing, a technique used to assess the horse’s energy field. This helps practitioners identify specific trapped emotions contributing to the horse’s issues.

- Releasing Emotions: Once identified, practitioners use a variety of methods to release these trapped emotions. This may include:

- Energy Healing: Techniques such as Reiki or simple hands-on healing to facilitate energy flow.

- Intentional Visualization: Guiding the horse through visualization exercises to help release the emotional burden.

- Balancing the Body: After releasing trapped emotions, the focus shifts to restoring balance within the horse’s body. This can involve addressing physical imbalances that may have been exacerbated by emotional stress.

Benefits of the Emotion Code for Horses

- Improved Behavior: Many horse owners report significant improvements in their horse’s behavior after undergoing Emotion Code sessions.

- Enhanced Bonding: The process fosters a deeper connection between horse and handler, promoting trust and understanding.

- Overall Well-Being: Addressing emotional issues can lead to better physical health, as stress and emotional turmoil can often manifest as physical ailments.

Creating a Supportive Environment

In addition to the Emotion Code, creating a nurturing and supportive environment is crucial for the horse’s healing journey:

- Consistency and Routine: Horses thrive on routine. Providing a stable environment helps reduce anxiety.

- Positive Reinforcement: Encourage desired behaviors through positive reinforcement techniques to build confidence and trust.

- Mindfulness Practices: Incorporate mindfulness into your interactions with the horse, fostering a calm and focused atmosphere.

Conclusion

The Emotion Code offers a powerful approach to healing horses by addressing the emotional factors that can influence their behavior and well-being. By recognizing and releasing trapped emotions, horse owners can enhance their equine companions’ quality of life, leading to happier, healthier horses. If you’re interested in exploring the Emotion Code for your horse, consider connecting with a trained practitioner to start the healing journey. Your horse deserves the chance to thrive free from emotional burdens!

Animals have emotions, too! Through the Emotion Code, trapped negative energies in the body can be released energetically.

Watch Video

The Link Between Somatic Healing, Trauma, and Horses

The Polyvagal Theory and Horses: An Introduction

“hopefully this provides a clearer understanding of not only the “what” of the polyvagal theory, but also the “why” (its relevance as a lens or framework through which to approach horses and horse-human interactions)” – By Sarah Schulte – Equusoma.

As research and our understanding of things evolve, so too does what we teach in EQUUSOMA®. The following is an excerpt of my book manuscript from 2019, which has since been updated in the current version of the manuscript, which will be in press with Routledge in 2023. We have commissioned specific illustrations that we now use in the EQUUSOMA® training and that will also be in the book. We’re in the process of updating our illustrations, including one that we just re-released today. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy the material below (as well as my 2018 post about the polyvagal theory in relation to horses licking and chewing), which is but an introduction to a rather complex and nuanced topic.

—-

This post has been a long time coming. The single reason as to why this has not gotten written yet is because I’ve been focusing my writing efforts on the book I have in the works (which includes this topic), that writing a separate blog post on the same subject felt like a repetitive task. However, it’s an important and complicated topic, well worth trying to explain in accessible terms. And there’s also no rule saying I can’t share material from my book in a blog post. And so, without further ado…

The Original Two-Branch Model

Before discussing the polyvagal theory and why it is foundational in understanding mammalian relationships and trauma recovery, it is worth looking back at our understanding of the nervous system as it stood until recently. Traditionally, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) has been taught as having two distinct branches – the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). This two-branch model has become ubiquitous and mainstream, and is still used by therapists, sports psychologists, coaches, riding instructors, equine behaviourists and other horse professionals. This perspective of the nervous system talks about sympathetic arousal, commonly known as the stress response (the body’s “gas pedal”), which involves the body’s ability to generate energy in order to meet the physiological or emotional demands of a particular situation. It is associated with a sense of capability and agency in taking effective action.

The SNS does not only refer to negative stressors that are more on the unpleasant end of the spectrum (such as uncomfortable situations or experiences of danger or life threat), but also more pleasant experiences of arousal (such as excitement, healthy sexuality, play and physical activity). Sympathetic arousal is also involved in eustress, experiences of arousal that are viewed as a positive or goal-oriented challenge inciting vigor, purposefulness and hope (such as more active or strenuous exercise, preparing for a major presentation, and so on). It is important to note that everyone experiences stressors differently; what is pleasant for one may be unpleasant for another.

Benson, Beary and Carol (1974) coined the term “relaxation response” to refer to the parasympathetic deactivation process that supports the organism to return to a resting state following exertion (the “brakes”). The brakes are released again in response to stress, danger or threat so that the SNS can kick in and mobilize energy required to meet the demands of a situation, and are re-engaged when the stressor has passed once more. The nervous system was thought to respond and calibrate moment to moment like this on a regular basis. A common expression from this model is “you can’t be stressed and relaxed at the same time”, meaning that finding balance involves coming out of a stress response and into a relaxation response. Some who hold this view, both in the human trauma field and the horse training field, sometimes interpret any signs of stress as being negative and evidence of distress, pain or confusion, and encourage avoiding things that increase stress, prioritizing “down-regulation” as desired and ideal. While this is not entirely untrue, it nonetheless is based on a limited understanding of stressors and disregards how stress can be useful and how excessive use of the parasympathetic nervous system can also be damaging. It also does not take into consideration the role of the vagus nerve in arousal modulation, relationships, and health issues.

From Two to Three

Neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges has conducted groundbreaking work on understanding the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in mammals. Among his contributions was the proposition that the ANS has three branches as opposed to two. Rather than one branch being on while the other was off, the three branches act more like dials, each on to varying degrees at the same time, and responding in a hierarchical manner in response to changing environmental conditions, moderated by the vagus nerve. This is actually much less complicated than it sounds.

To begin, mammals have what Porges refers to as neuroception, or the ability to detect safety, danger or life threat. Depending on what internal (interoception) and external (exteroception) cues an organism picks up on, corresponding adaptive neural adaptations (or responses) will kick in. Typically, we’ll respond to danger or life threat by using our most recently developed strategies first, and gradually move down the line to using evolutionarily older, more primitive responses if we’re unsuccessful. Let’s start in reverse, with oldest first.

- Dorsal vagal complex (DVC): The DVC is thought to be the most primitive branch of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) and is responsible for immobilization. This response to potential dangers, intrusions, shock, toxins, overwhelm, abandonment or other painful experiences stems back not only to reptiles but can also be witnessed in amoebas and even in protoplasm, the basis for all life (Seifriz, 1954). The DVC is responsible for what is most commonly referred to as the freeze response (tonic or rigid immobility), but also is involved in fold (collapsed immobility), faint (vasovagal syncope), and feigning death. Fragmentation (or dissociation) is also common when organisms are dominated by the DVC, as in “if I can’t get my body to safety, or if it’s not safe being me, then I’ll just leave my body”. Or, as actor Woody Allen famously quipped, “I’m not afraid of death – I just don’t want to be there when it happens.” Dorsal dominance means that the dorsal vagus “dial” is on high (shutdown and energy conservation, when the brakes are slammed on really hard). However, the parasympathetic nervous system is also involved in relaxation or settling; this would be when the dorsal vagus “dial” is on low (also known as “rest and digest” – immobility states where the brakes are applied much more gently, that are involved when meditating, sleeping, nursing, etc.).

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS): This response is responsible for mobilization. Arousal of various kinds stems from the SNS, including what one might consider to be pleasurable or enjoyable (fun) such as play, sex, excitement, going for a walk or jog, exercise, anticipating the visit of a loved one or preparing a meal, and so on. The SNS is also involved in run of the mill physical activity, such as getting out of bed, doing chores, making dinner, and so on. Of course, the SNS is also responsible for survival activation, such as fight or flight. This is the proverbial gas pedal and is also associated with the tensing and tightening associated with preparing for activity and self-protective movements, ranging from posturing, intimidation, pushing, punching, kicking, to moving or running away, and so on. It is important to note that not all SNS arousal is survival activation; all activation is, however, arousal. SNS functions like a dial as well, from low to high, and it is moderated by both branches of the PNS (the dorsal brake and the ventral brake).

- Ventral vagal complex (VVC): Social engagement is the second branch of the parasympathetic nervous system. Similar to low tone DVC, the VVC is a gentler brake system; it slows the heart down and supports connection (“freedom, friends and forage” are the most possible when dominated by a low tone DVC or a VVC state — this does not mean that there is no SNS onboard, however. For instance, horses can be playing with their friends at liberty in an open pasture. The VVC “dial” provides the brakes that tempers the SNS just enough that play is fun and does not flip into fight or flight activation). The ventral vagal branch of the PNS also “allows social interactions to regulate physiology and promotes health, growth and restoration” (Porges, 2018b).Furthermore, when anticipating danger or threat, mammals may turn to social engagement strategies for soothing and protection (finding resources: AKA ‘tend and befriend’, consisting of attachment cry, clinging, proximity seeking, bunching, cohesion, protesting separation) or to defuse tension and aggression and prevent harm (fawn: also known as “tend and befriend”, including appeasement behaviours such as reasoning, caretaking, placating, complying, and so on). There are preparatory movements involved in this category of response pattern as well, such as turning towards and reaching for others.Should social engagement prove successful, and the “other” is seen as receptive or supportive or begins to calm down, our own nervous system calms as well and we are able to remain in social connection. However, should social engagement strategies not be effective, fighting or fleeing become the next resort and, should these also not be available or possible, that leaves shutdown as the final option. This is known as dissolution, which was first described by Jackson (1884), who stated that “the higher nervous arrangements inhibit the lower, and thus, when the higher are suddenly rendered functionless, the lower rise in activity”.It is difficult to envision these three branches functioning to various degrees at the same time in the above graph. Graphs are imperfect attempts at conveying complex concepts in simplified ways, but are still useful nonetheless. My best attempt at showing how the three states operate in overlapping ways (as opposed to being completely mutually exclusive) was in using the shaded gradients. For instance, when we are in a state of ventral vagal dominance (the VVC branch of the PNS), there is usually no dorsal vagal activity on board (the other branch of the PNS is off); however, there can be varying degrees of sympathetic arousal present while in a ventral vagal state. The example of play is one of them. The VVC being on helps mitigate the potentially negative impact of SNS arousal which, if experienced without a sense of safe connection in relationship, can escalate to higher levels and potential shutdown through the dorsal vagal branch of the PNS as the only remaining option. This aligns with attachment theory, in that co-regulation through social engagement (when two nervous systems are in sync in the window of tolerance) is an important component of moderating SNS arousal. Attunement and co-regulation helps our bodies experience that “what goes up must (and will) come down” when the right conditions are in place.This graph also depicts the concept of “as they go in, so they come out“. Dr. Peter Levine, developer of the Somatic Experiencing approach to trauma resolution, describes how this term was originally used in reference to military veterans who went into a freeze response following intense fight or flight activation. These veterans eventually thawed out of freeze and came back down through the same SNS charge that they experienced prior to shutting down, exhibiting sudden aggression, combativeness, or flight responses following a period of apparent stability (Levine, 2010). In other words, when the nervous system begins to experience the neuroception of safety, it can begin to “let down” and move through all the bound activation that was held in the queue in order to regain balance. This process can also occur when we come in and out of anesthetic for surgery, and is common in survivors of childhood abuse, partner abuse, and other traumatic events.Numerous videos depict animals coming in and out of the dorsal vagal shutdown in this way as well. A few of them can be found here. Others can be found saved in my playlist of educational videos on the EQUUSOMA YouTube channel. In horses, it is most commonly seen when a horse has experienced training methods or abuse that resulted in learned helplessness and submission. When the right conditions are in place and the horse is able to “thaw out of freeze”, the incomplete survival responses (fight or flight activation) that are lying just under that dorsal state often emerge in dramatic ways as a horse suddenly becomes more opinionated, flighty, or aggressive after being seemingly docile and “bombproof” for a long time. Because the parasympathetic NS has two branches (two brake systems), it is easy to confuse one for the other: dissociation, submission, stoicism, and shutdown may “look calm” on the surface, but are really a sign of the high tone dorsal brake being on to try to control the undercurrents of overwhelm or flooding. “True calm” comes from the low tone dorsal brake (rest and digest) or the ventral vagal brake (social engagement), which are at the bottom of the graph and occur following deactivation or “discharge” of the higher states of arousal or activation.

Thresholds of Intensity

This does not mean to imply that the sequence always takes place the way the graph shows. Dorsal vagal shutdown does not always occur just because a mammal is experiencing higher SNS arousal or activation. The curve can peak and drop at various levels of intensity without ever reaching the high tone DVC state of shutdown.

Similarly, this does not always mean that the goal is to limit any kind of SNS arousal, because not all SNS arousal is detrimental to the nervous system. If that was the case, then trauma therapy (in humans, at least, but I would argue for other mammals as well) would consist of nothing more than teaching grounding skills to manage bound activation in the nervous system that is stuck in the queue, never having a chance to be released. Somatic Experiencing, as a polyvagal-informed approach to trauma recovery grounded in mammalian neuroscience, emphasizes how grounding skills and other techniques to prevent or limit activation is only one part of the picture. The over-arching goal is not to continually avoid stress, as this results in a narrow window of tolerance, but to grow the window and one’s resilience by learning that the nervous system can experience fluctuations without going into shutdown.

Someone recently told me “the reason I use positive reinforcement is because I recognize that domesticated horses experience a lot of stress that is out of their control, and so I don’t want to add more stress to their existing load through training methods that use aversives” (as in negative reinforcement, or pressure-release). There is a certain amount of validity to this perspective. Similar to trauma therapy with humans, if the conditions are not optimal (as in, the conditions are not safe and supporting regulation and coherence in the nervous system), then it is not the time to do the harder work of trauma processing (which can be more activating). However, when the conditions are “good enough” (there is enough safety and stability both internally and externally), then dipping into the deeper stuff can be attempted, to help de-activate the bound charge that is still held in the body and to grow the window of tolerance.

Bear in mind, that there is a difference between therapies that encourage flooding and therapies that focus on the titrated renegotiation of little incremental amounts of survival activation to grow the window of tolerance. Just because the conditions are right doesn’t mean that flooding is ever appropriate (if your goal is to induce compliance, then that’s another story). Titration is still crucial to not send someone into overwhelm, which is simply a re-enactment of retraumatization. Similarly, there are horse training techniques that encourage flooding (most often methods that mis-use negative reinforcement to dominate and induce learned helplessness) and those that are more nuanced and attend to these thresholds of intensity in order to help grow the window of tolerance. Both negative and positive reinforcement can be done with this perspective in mind.

There is a big difference between negative reinforcement done to dominate and shut down (sending the horse into the “red zone” of the graph above), and negative reinforcement that is done while attending to thresholds, nervous system states, and that uses connection and the social engagement system (ventral vagal branch of the PNS) to moderate arousal so that it is not detrimental. We grow the window of tolerance by recognizing that what goes up will come down, and by helping the nervous system tolerate incrementally bigger thresholds without getting stuck in fight or flight activation or shutdown.

The Fed Up Fred illustration on thresholds explains this in more simple terms. Not all negative reinforcement (-R) is above threshold. Negative reinforcement that is below threshold is not necessarily detrimental to the horse. Negative reinforcement that goes above threshold (i.e., into a high degree of SNS without a ventral brake, or into high tone DVC shutdown) is problematic. What the polyvagal theory and Somatic Experiencing can add to this picture is the idea that it’s maybe not as simple as “show the desired behaviour and you will be allowed to escape or avoid the scary thing”. That implies tolerating and overriding. Instead, the goal is to experience a pendulation of the nervous system in response to a tiny stimulus (a pendulation is the full arousal and settling of the ANS) to recognize “oh, this isn’t so bad”, before the window of tolerance grows a little to allow a little more — without stimulus stacking and resorting to escape or avoidance to cope. This, in turn, builds confidence and resilience. It is the difference between reliving and what Dr. Peter Levine calls renegotiation:

“Renegotiation is not about simply reliving a traumatic experience. It is, rather, the gradual and titrated revisiting of various sensory-motor elements comprising a particular trauma. Renegotiation occurs primarily by accessing procedural memories associated with the two dysregulated states of the autonomic nervous system (hyper/hypo-arousal) and then restoring and completingthe associated active responses. As this progresses, the client moves towards equilibrium, relaxed alertness, and here-and-now orientation.”

–Levine (2015, p. 44)

Of course, Somatic Experiencing is not a recognized training method for horses. Although it was developed for human trauma recovery, it nonetheless draws on mammalian neuroscience, so there is some validity to the notion that it (or elements of it) could be used with horses as well, albeit in adapted ways. My sample size of using it with my own horses as well as with horses I work with in equine-assisted trauma recovery is not sufficient to claim evidence-based practice, of course! Nor am I an equine behaviourist. Similarly, Dr. Stephen Porges is not a trauma therapist; however, his ideas have been enthusiastically adopted by the trauma therapy community because of how useful they are in predicting what we see happening and in helping guide interventions in a more effective way. Similarly, I see the potential for the polyvagal theory being a useful framework for the equine sciences, equestrian, and equine-assisted interventions fields.The Polyvagal Theory and Horses: An Introduction

**March 24, 2022 Note: As research and our understanding of things evolve, so too does what we teach in EQUUSOMA®. The following is an excerpt of my book manuscript from 2019, which has since been updated in the current version of the manuscript, which will be in press with Routledge in 2023. We have commissioned specific illustrations that we now use in the EQUUSOMA® training and that will also be in the book. We’re in the process of updating our illustrations, including one that we just re-released today. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy the material below (as well as my 2018 post about the polyvagal theory in relation to horses licking and chewing), which is but an introduction to a rather complex and nuanced topic.

—-

This post has been a long time coming. The single reason as to why this has not gotten written yet is because I’ve been focusing my writing efforts on the book I have in the works (which includes this topic), that writing a separate blog post on the same subject felt like a repetitive task. However, it’s an important and complicated topic, well worth trying to explain in accessible terms. And there’s also no rule saying I can’t share material from my book in a blog post. And so, without further ado…

The Original Two-Branch Model

Before discussing the polyvagal theory and why it is foundational in understanding mammalian relationships and trauma recovery, it is worth looking back at our understanding of the nervous system as it stood until recently. Traditionally, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) has been taught as having two distinct branches – the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). This two-branch model has become ubiquitous and mainstream, and is still used by therapists, sports psychologists, coaches, riding instructors, equine behaviourists and other horse professionals. This perspective of the nervous system talks about sympathetic arousal, commonly known as the stress response (the body’s “gas pedal”), which involves the body’s ability to generate energy in order to meet the physiological or emotional demands of a particular situation. It is associated with a sense of capability and agency in taking effective action.

The SNS does not only refer to negative stressors that are more on the unpleasant end of the spectrum (such as uncomfortable situations or experiences of danger or life threat), but also more pleasant experiences of arousal (such as excitement, healthy sexuality, play and physical activity). Sympathetic arousal is also involved in eustress, experiences of arousal that are viewed as a positive or goal-oriented challenge inciting vigor, purposefulness and hope (such as more active or strenuous exercise, preparing for a major presentation, and so on). It is important to note that everyone experiences stressors differently; what is pleasant for one may be unpleasant for another.

Benson, Beary and Carol (1974) coined the term “relaxation response” to refer to the parasympathetic deactivation process that supports the organism to return to a resting state following exertion (the “brakes”). The brakes are released again in response to stress, danger or threat so that the SNS can kick in and mobilize energy required to meet the demands of a situation, and are re-engaged when the stressor has passed once more. The nervous system was thought to respond and calibrate moment to moment like this on a regular basis. A common expression from this model is “you can’t be stressed and relaxed at the same time”, meaning that finding balance involves coming out of a stress response and into a relaxation response. Some who hold this view, both in the human trauma field and the horse training field, sometimes interpret any signs of stress as being negative and evidence of distress, pain or confusion, and encourage avoiding things that increase stress, prioritizing “down-regulation” as desired and ideal. While this is not entirely untrue, it nonetheless is based on a limited understanding of stressors and disregards how stress can be useful and how excessive use of the parasympathetic nervous system can also be damaging. It also does not take into consideration the role of the vagus nerve in arousal modulation, relationships, and health issues.

From Two to Three

Neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges has conducted groundbreaking work on understanding the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in mammals. Among his contributions was the proposition that the ANS has three branches as opposed to two. Rather than one branch being on while the other was off, the three branches act more like dials, each on to varying degrees at the same time, and responding in a hierarchical manner in response to changing environmental conditions, moderated by the vagus nerve. This is actually much less complicated than it sounds.

To begin, mammals have what Porges refers to as neuroception, or the ability to detect safety, danger or life threat. Depending on what internal (interoception) and external (exteroception) cues an organism picks up on, corresponding adaptive neural adaptations (or responses) will kick in. Typically, we’ll respond to danger or life threat by using our most recently developed strategies first, and gradually move down the line to using evolutionarily older, more primitive responses if we’re unsuccessful. Let’s start in reverse, with oldest first.

- Dorsal vagal complex (DVC): The DVC is thought to be the most primitive branch of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) and is responsible for immobilization. This response to potential dangers, intrusions, shock, toxins, overwhelm, abandonment or other painful experiences stems back not only to reptiles but can also be witnessed in amoebas and even in protoplasm, the basis for all life (Seifriz, 1954). The DVC is responsible for what is most commonly referred to as the freeze response (tonic or rigid immobility), but also is involved in fold (collapsed immobility), faint (vasovagal syncope), and feigning death. Fragmentation (or dissociation) is also common when organisms are dominated by the DVC, as in “if I can’t get my body to safety, or if it’s not safe being me, then I’ll just leave my body”. Or, as actor Woody Allen famously quipped, “I’m not afraid of death – I just don’t want to be there when it happens.” Dorsal dominance means that the dorsal vagus “dial” is on high (shutdown and energy conservation, when the brakes are slammed on really hard). However, the parasympathetic nervous system is also involved in relaxation or settling; this would be when the dorsal vagus “dial” is on low (also known as “rest and digest” – immobility states where the brakes are applied much more gently, that are involved when meditating, sleeping, nursing, etc.).

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS): This response is responsible for mobilization. Arousal of various kinds stems from the SNS, including what one might consider to be pleasurable or enjoyable (fun) such as play, sex, excitement, going for a walk or jog, exercise, anticipating the visit of a loved one or preparing a meal, and so on. The SNS is also involved in run of the mill physical activity, such as getting out of bed, doing chores, making dinner, and so on. Of course, the SNS is also responsible for survival activation, such as fight or flight. This is the proverbial gas pedal and is also associated with the tensing and tightening associated with preparing for activity and self-protective movements, ranging from posturing, intimidation, pushing, punching, kicking, to moving or running away, and so on. It is important to note that not all SNS arousal is survival activation; all activation is, however, arousal. SNS functions like a dial as well, from low to high, and it is moderated by both branches of the PNS (the dorsal brake and the ventral brake).

- Ventral vagal complex (VVC): Social engagement is the second branch of the parasympathetic nervous system. Similar to low tone DVC, the VVC is a gentler brake system; it slows the heart down and supports connection (“freedom, friends and forage” are the most possible when dominated by a low tone DVC or a VVC state — this does not mean that there is no SNS onboard, however. For instance, horses can be playing with their friends at liberty in an open pasture. The VVC “dial” provides the brakes that tempers the SNS just enough that play is fun and does not flip into fight or flight activation). The ventral vagal branch of the PNS also “allows social interactions to regulate physiology and promotes health, growth and restoration” (Porges, 2018b).Furthermore, when anticipating danger or threat, mammals may turn to social engagement strategies for soothing and protection (finding resources: AKA ‘tend and befriend’, consisting of attachment cry, clinging, proximity seeking, bunching, cohesion, protesting separation) or to defuse tension and aggression and prevent harm (fawn: also known as “tend and befriend”, including appeasement behaviours such as reasoning, caretaking, placating, complying, and so on). There are preparatory movements involved in this category of response pattern as well, such as turning towards and reaching for others.Should social engagement prove successful, and the “other” is seen as receptive or supportive or begins to calm down, our own nervous system calms as well and we are able to remain in social connection. However, should social engagement strategies not be effective, fighting or fleeing become the next resort and, should these also not be available or possible, that leaves shutdown as the final option. This is known as dissolution, which was first described by Jackson (1884), who stated that “the higher nervous arrangements inhibit the lower, and thus, when the higher are suddenly rendered functionless, the lower rise in activity”.

Hierarchical ANS Responses

Illustration by Carolyn Buck Reynolds. All rights reserved. Updated in 2021.

It is difficult to envision these three branches functioning to various degrees at the same time in the above graph. Graphs are imperfect attempts at conveying complex concepts in simplified ways, but are still useful nonetheless. My best attempt at showing how the three states operate in overlapping ways (as opposed to being completely mutually exclusive) was in using the shaded gradients. For instance, when we are in a state of ventral vagal dominance (the VVC branch of the PNS), there is usually no dorsal vagal activity on board (the other branch of the PNS is off); however, there can be varying degrees of sympathetic arousal present while in a ventral vagal state. The example of play is one of them. The VVC being on helps mitigate the potentially negative impact of SNS arousal which, if experienced without a sense of safe connection in relationship, can escalate to higher levels and potential shutdown through the dorsal vagal branch of the PNS as the only remaining option. This aligns with attachment theory, in that co-regulation through social engagement (when two nervous systems are in sync in the window of tolerance) is an important component of moderating SNS arousal. Attunement and co-regulation helps our bodies experience that “what goes up must (and will) come down” when the right conditions are in place.

This graph also depicts the concept of “as they go in, so they come out“. Dr. Peter Levine, developer of the Somatic Experiencing approach to trauma resolution, describes how this term was originally used in reference to military veterans who went into a freeze response following intense fight or flight activation. These veterans eventually thawed out of freeze and came back down through the same SNS charge that they experienced prior to shutting down, exhibiting sudden aggression, combativeness, or flight responses following a period of apparent stability (Levine, 2010). In other words, when the nervous system begins to experience the neuroception of safety, it can begin to “let down” and move through all the bound activation that was held in the queue in order to regain balance. This process can also occur when we come in and out of anesthetic for surgery, and is common in survivors of childhood abuse, partner abuse, and other traumatic events.

Numerous videos depict animals coming in and out of the dorsal vagal shutdown in this way as well. A few of them can be found here. Others can be found saved in my playlist of educational videos on the EQUUSOMA YouTube channel. In horses, it is most commonly seen when a horse has experienced training methods or abuse that resulted in learned helplessness and submission. When the right conditions are in place and the horse is able to “thaw out of freeze”, the incomplete survival responses (fight or flight activation) that are lying just under that dorsal state often emerge in dramatic ways as a horse suddenly becomes more opinionated, flighty, or aggressive after being seemingly docile and “bombproof” for a long time. Because the parasympathetic NS has two branches (two brake systems), it is easy to confuse one for the other: dissociation, submission, stoicism, and shutdown may “look calm” on the surface, but are really a sign of the high tone dorsal brake being on to try to control the undercurrents of overwhelm or flooding. “True calm” comes from the low tone dorsal brake (rest and digest) or the ventral vagal brake (social engagement), which are at the bottom of the graph and occur following deactivation or “discharge” of the higher states of arousal or activation.

Thresholds of Intensity

This does not mean to imply that the sequence always takes place the way the graph shows. Dorsal vagal shutdown does not always occur just because a mammal is experiencing higher SNS arousal or activation. The curve can peak and drop at various levels of intensity without ever reaching the high tone DVC state of shutdown.

©Hoskinson Consulting Inc. d/b/a Organic Intelligence. All rights reserved. Used with permission. Model developed by Steve Hoskinson for Somatic Experiencing training. Similarly, this does not always mean that the goal is to limit any kind of SNS arousal, because not all SNS arousal is detrimental to the nervous system. If that was the case, then trauma therapy (in humans, at least, but I would argue for other mammals as well) would consist of nothing more than teaching grounding skills to manage bound activation in the nervous system that is stuck in the queue, never having a chance to be released. Somatic Experiencing, as a polyvagal-informed approach to trauma recovery grounded in mammalian neuroscience, emphasizes how grounding skills and other techniques to prevent or limit activation is only one part of the picture. The over-arching goal is not to continually avoid stress, as this results in a narrow window of tolerance, but to grow the window and one’s resilience by learning that the nervous system can experience fluctuations without going into shutdown.

Someone recently told me “the reason I use positive reinforcement is because I recognize that domesticated horses experience a lot of stress that is out of their control, and so I don’t want to add more stress to their existing load through training methods that use aversives” (as in negative reinforcement, or pressure-release). There is a certain amount of validity to this perspective. Similar to trauma therapy with humans, if the conditions are not optimal (as in, the conditions are not safe and supporting regulation and coherence in the nervous system), then it is not the time to do the harder work of trauma processing (which can be more activating). However, when the conditions are “good enough” (there is enough safety and stability both internally and externally), then dipping into the deeper stuff can be attempted, to help de-activate the bound charge that is still held in the body and to grow the window of tolerance.

Bear in mind, that there is a difference between therapies that encourage flooding and therapies that focus on the titrated renegotiation of little incremental amounts of survival activation to grow the window of tolerance. Just because the conditions are right doesn’t mean that flooding is ever appropriate (if your goal is to induce compliance, then that’s another story). Titration is still crucial to not send someone into overwhelm, which is simply a re-enactment of retraumatization. Similarly, there are horse training techniques that encourage flooding (most often methods that mis-use negative reinforcement to dominate and induce learned helplessness) and those that are more nuanced and attend to these thresholds of intensity in order to help grow the window of tolerance. Both negative and positive reinforcement can be done with this perspective in mind.

There is a big difference between negative reinforcement done to dominate and shut down (sending the horse into the “red zone” of the graph above), and negative reinforcement that is done while attending to thresholds, nervous system states, and that uses connection and the social engagement system (ventral vagal branch of the PNS) to moderate arousal so that it is not detrimental. We grow the window of tolerance by recognizing that what goes up will come down, and by helping the nervous system tolerate incrementally bigger thresholds without getting stuck in fight or flight activation or shutdown.

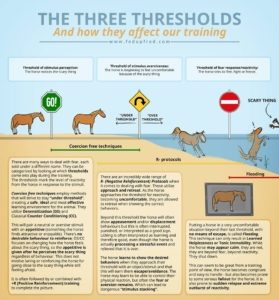

© Fed Up Fred – The Three Thresholds The Fed Up Fred illustration on thresholds explains this in more simple terms. Not all negative reinforcement (-R) is above threshold. Negative reinforcement that is below threshold is not necessarily detrimental to the horse. Negative reinforcement that goes above threshold (i.e., into a high degree of SNS without a ventral brake, or into high tone DVC shutdown) is problematic. What the polyvagal theory and Somatic Experiencing can add to this picture is the idea that it’s maybe not as simple as “show the desired behaviour and you will be allowed to escape or avoid the scary thing”. That implies tolerating and overriding. Instead, the goal is to experience a pendulation of the nervous system in response to a tiny stimulus (a pendulation is the full arousal and settling of the ANS) to recognize “oh, this isn’t so bad”, before the window of tolerance grows a little to allow a little more — without stimulus stacking and resorting to escape or avoidance to cope. This, in turn, builds confidence and resilience. It is the difference between reliving and what Dr. Peter Levine calls renegotiation:

“Renegotiation is not about simply reliving a traumatic experience. It is, rather, the gradual and titrated revisiting of various sensory-motor elements comprising a particular trauma. Renegotiation occurs primarily by accessing procedural memories associated with the two dysregulated states of the autonomic nervous system (hyper/hypo-arousal) and then restoring and completingthe associated active responses. As this progresses, the client moves towards equilibrium, relaxed alertness, and here-and-now orientation.”

–Levine (2015, p. 44)

Of course, Somatic Experiencing is not a recognized training method for horses. Although it was developed for human trauma recovery, it nonetheless draws on mammalian neuroscience, so there is some validity to the notion that it (or elements of it) could be used with horses as well, albeit in adapted ways. My sample size of using it with my own horses as well as with horses I work with in equine-assisted trauma recovery is not sufficient to claim evidence-based practice, of course! Nor am I an equine behaviourist. Similarly, Dr. Stephen Porges is not a trauma therapist; however, his ideas have been enthusiastically adopted by the trauma therapy community because of how useful they are in predicting what we see happening and in helping guide interventions in a more effective way. Similarly, I see the potential for the polyvagal theory being a useful framework for the equine sciences, equestrian, and equine-assisted interventions fields.

Poly-what? Why?

This brings us back to that infamous word. The reason this is called the polyvagal (or multiple vagi) theory is that the tenth cranial nerve (known as the vagus, or “vagabond”) is also the longest and wanders far and wide, linking up with a number of different parts of the face and body. The parasympathetic nervous system’s two branches (DVC and VVC) come on depending on which part of the vagus is firing at any given point in response to internal and external conditions. For instance:

- The ventral vagus links the muscles of the face and neck, larynx and pharynx (involved in speech), and heart (“supra-diaphragmatic” or above the respiratory diaphragm). These parts of the body are involved in social communication and connection. When this part of the vagus is online or dominating, the face is engaged, eyes are soft or show aliveness and variability of expression, vocalizations or talking are feasible, and heart rate slows to a comfortable pace that allows a sense of comfort or ease in connection. Presence is possible. This is why the ventral vagus is known as the social engagement system. A nervous system that is dominated by a ventral vagal state has a very different facial expression than one that is dominated by a high level of SNS or a high level of DVC. There are even differences in facial expression between humans and horses that are in a high level of SNS arousal that is tempered by the ventral vagal brake (as in play) and humans and horses that are in a high level of SNS arousal tipping into survival activation (as in fighting).As seen in the diagram below, the vagus is intimately linked with the other cranial nerves, including those that innervate the middle ear. When detecting the neuroception of danger or life threat, for instance, the middle ear will focus on sound frequencies like low grumbles, growls, stampeding hooves, equipment noises, and so on, making it difficult to pay attention to the vocal frequencies of the human voice. It is one of the reasons why in arguments it can difficult to really hear what someone else is saying.

- The dorsal vagus links the larynx and pharynx with the heart and the gut (operates largely “sub-diaphragmatic” or below the respiratory diaphragm). When a high tone dorsal vagal state is dominating, the parts of the body involved in social communication and connection go offline because the ventral vagus (above the diaphragm) is off; the face has a flat expression, eyes may appear vacant or empty, vocalizations or talking are not possible or difficult to make. A high tone dorsal state of shutdown is useful for survival, but is not intended to be the main brake system – think of it like driving a car using your hand brake whenever you want to slow down. The amount of wear and tear would be significant and your car would become run down very quickly. Indeed, human and non-human animals that have become dominated by this shutdown state as a response to threat or overwhelm often have issues in the parts of the body that are innervated by the dorsal vagus – namely heart, gastrointestinal, and feeding or eating-related issues or disorders. Instead, we want to slow down using the low tone dorsal brake (a foot brake that supports restfulness) or the ventral brake (which supports comfort in connection).

In the last of the images, the ventral vagus is mapped in blue, the dorsal vagus is mapped in red, and the sympathetic nervous system is in gold. Imagine these three colours superimposed over the full body diagram of the horse above, and you get a reasonable comparison. In short, the neuroception of safety supports the ventral vagus to come back online. It also supports the state of low tone dorsal vagal “rest and digest”. What can shift a nervous system from sensing “safety” to sensing “threat” can be incredibly subtle. So often we assume “bad behaviour” when in fact what we are seeing is a nervous system response to danger.

Copyright John Chitty, Colorado School of Energy Studies

Nervous System Dials

Technically, it is possible to “be stressed and relaxed at the same time” – if we look at things through a polyvagal lens, where the PNS can be used to temper the experience of the SNS. To give a better sense of the idea of how the 3 branches of the ANS function together as fluctuating dials, consider the following examples:

- Petting a cat. This is an enjoyable experience until the cat appears to suddenly turn on you and sinks its teeth and claws into your hand. The original experience likely was calming and involved a certain amount of social engagement (low DVC, moderate VVC, low SNS), but as the stroking became overstimulating, VVC would have decreased to low, DVC might increase a little as the cat disconnected, and SNS would have started to increase to higher levels, culminating in the attack. This is similar to when one person tickles another and it’s still within one’s window of tolerance; DVC is low, and there is a good amount of VVC online to temper the SNS response. However, should the tickler fail to recognize the other person’s threshold and continue even though the person is overstimulated, the game can quickly result in a drop in VVC engagement, increasing SNS, and an increase in DVC (shouting and/or pushing, or shutdown and withdrawing when it is clear the tickler isn’t getting the message).

- This is similar to the question of sex. Sex that is connected and intimate (not just the mechanical act) typically would involve low tone DVC, moderate to high VVC, and low to moderate SNS, depending on how vigorous or charged the encounter was (sex that was purely physical with no connection would involve low VVC). However, when sex becomes rape, the dials would change to high tone DVC (shutdown, dissociation), low VVC (disconnection), and high SNS (fear).

- Savasana at the end of a yoga practice (the quiet period before going home, where people lie on their mats and rest): this would typically involve low amounts of DVC, low VVC and low SNS. For some individuals, however, the stillness of savasana can be activating, in which case savasana would more likely consist of potentially higher tone DVC, low VVC (no one to socially engage with to co-regulate), and high SNS.

- A kitten, squirrel, or mouse being carried by the scruff of the neck by its mother. This would involve high DVC (collapsed immobility; floppy tone), low to moderate VVC, and low SNS. Because of the absence of fear, the experience of letting go in this way might feel neutral, calming or even pleasurable; when the baby is put down again, muscle tone returns and the animal continues to play, explore and engage the way it did before being picked up. However, a gazelle held in the jaws of a predator might seem like a similar experience, but the dials here would be different: likely high DVC, low VVC, but high SNS (fear).

Consider the tragic media report of the horse that died from fright as a result of an unexpected fireworks display nearby (Bellis & Hawkins, 2018). Interestingly, there had been a planned fireworks display in the neighbourhood the previous week, and the horse’s owner had brought him indoors and stayed with him to help him remain calm (VVC or social engagement to mitigate the effects of stress). The horse recovered from that situation without issue. However, the owner had not been made aware that there would be another fireworks display on that fateful night a week later, and so the horse, named Solo, had been turned out alone without the ability to calm himself through ventral vagal engagement with other herd members or even a human nervous system to support co-regulation. And so, in the face of intense panic, distress, and inability to get away from the noise (high SNS mobilized to flee), the only way for the nervous system to slow down was to resort to the emergency hand brake (DVC), which has a high cost to the body: the horse’s gut had twisted (a possible sign of dorsal dominance following high stress) following running at top speed in his paddock for a prolonged period, and was in so much pain from the shock that he had to be put down. There was no ventral brake available to modulate the intensity of the terror to reduce the impact of the stimulus to the nervous system.

As devastating as this example is, it highlights how the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), typically thought of as the body’s relaxation response, is not always restorative in function. It is for this reason, and the others outlined above, that moving away from the earlier understanding of the nervous system as having two branches is not only helpful but necessary to understanding human-horse behaviour dynamics in a more nuanced way. The polyvagal model proposed by Dr. Porges offers a framework to help make sense of interactions and guide ways we might intervene differently, whether we are horse lovers or owners, riding coaches, equestrians, equine-assisted therapy and learning professionals, equine behaviourists, horse trainers, or other animal professionals. This will be elaborated on throughout the book… (in progress!)

—

Thanks for your patience, everyone. The book is coming. In the meantime, hopefully this provides a clearer understanding of not only the “what” of the polyvagal theory, but also the “why” (its relevance as a lens or framework through which to approach horses and horse-human interactions). There is more to it, but this is just a starting place to pique your curiosity.